In his 2006 short-story collection Tales of the Out & the Gone, Amiri Baraka details the Afrofuturist concept of “rhythm travel,” in which a man can journey within refrains of music to legacies past, present, and future. It’s a powerful piece of speculative fiction rooted in concepts Baraka previously articulated in Blues People, a seminal study of how Delta blues and its immediate descendants are situated in the seat of modern Black history.

It’s no surprise director Ryan Coogler took the time to study Baraka’s work as he developed the script for his new box-office hit, Sinners. The horror film is constructed around a deep reverence for the blues, its resonance within Black communities, and the looming threat of its exploitation. In a particularly arresting moment, that lineage is made explicit as Miles Caton’s Sammie performs the powerfully haunting “I Lied to You,” which traces the ancestral roots of the genre back to Africa, before flashing forward to its many descendants. “I let my spirit move me through the different phases, from hip-hop to The Hawkins Family,” says veteran songwriter Raphael Saadiq, who wrote the track alongside composer Ludwig Göransson. “I really am just a vessel.”

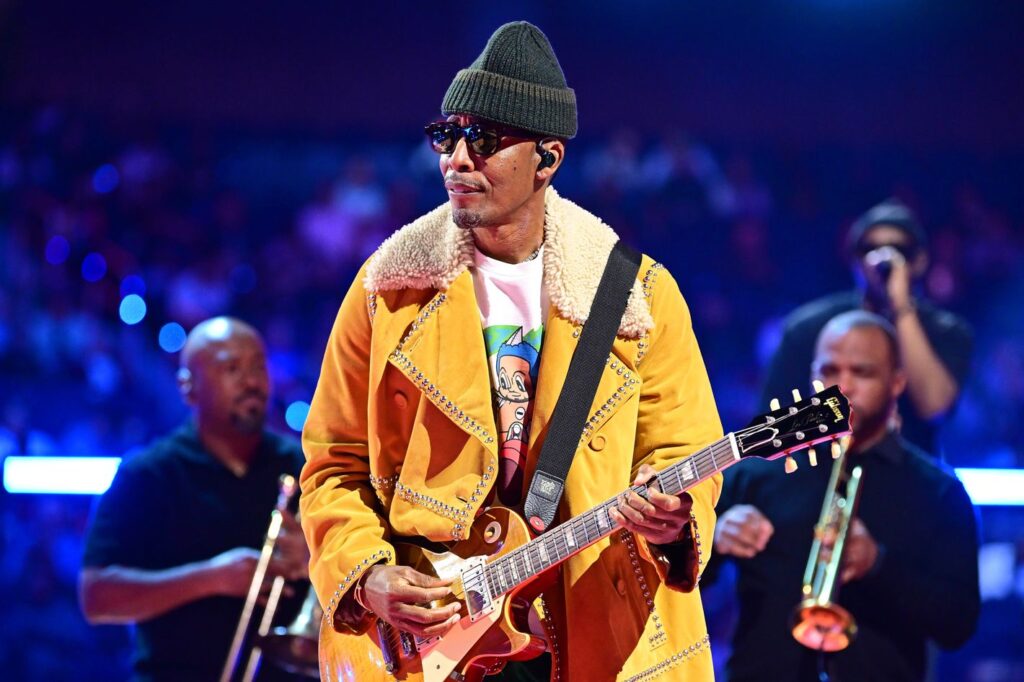

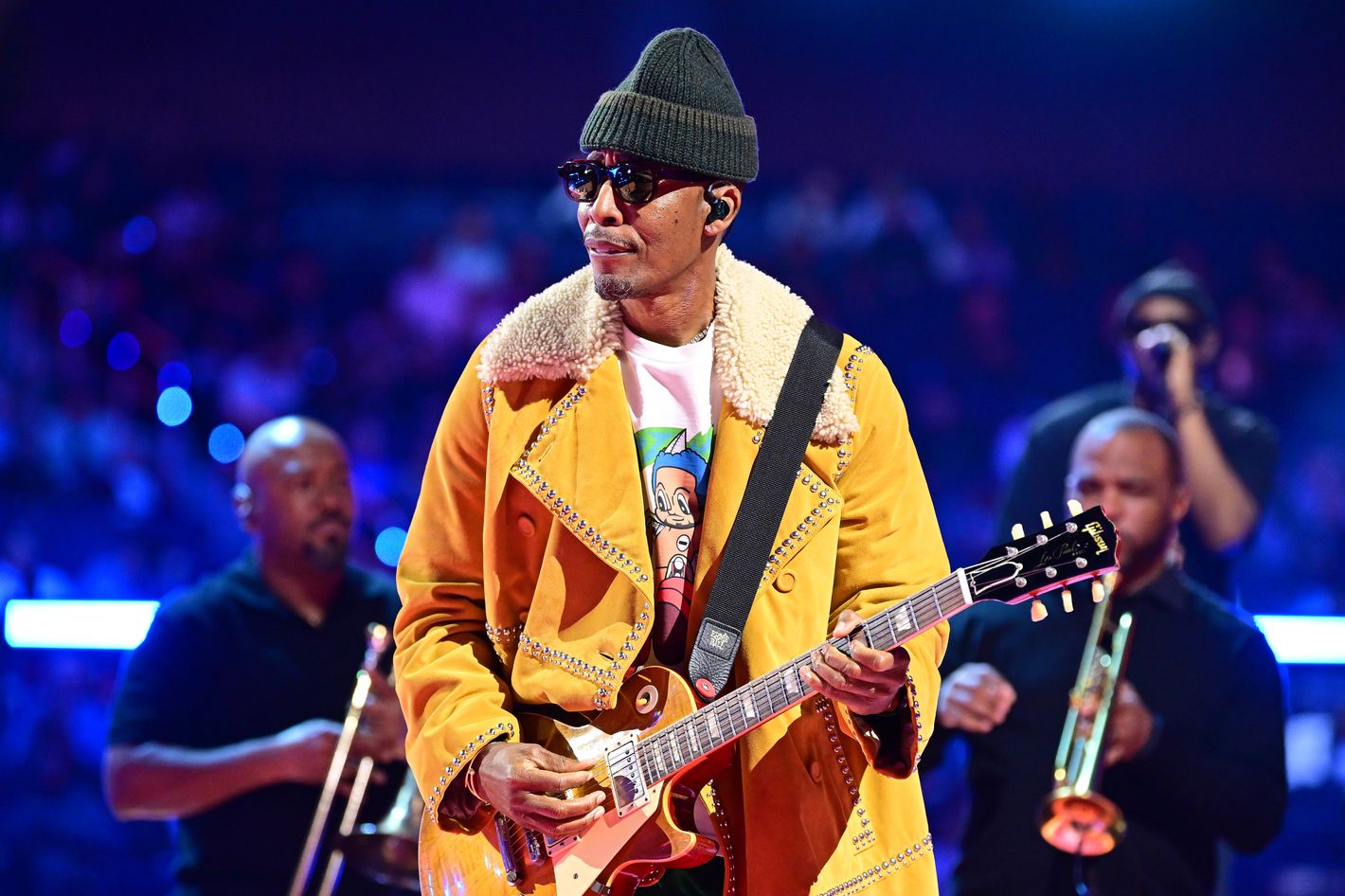

Saadiq is no stranger to making music across multiple genres, with a deep archive of hits that spans funk, soul, R&B, and country. The veteran singer-songwriter’s storied career has always centered a vast array of Black music, which made collaborating on an original song celebrating the blues and everything in between an organic next step. “Sidney Poitier once said to me that you have an accountability and responsibility,” Saadiq says. “I’ve done a lot, but there’s always more you can add and build.”

How did you get involved in Sinners?

Ryan Coogler and I are from the Bay Area. My late brother D’Wayne Wiggins and Ryan’s father went to school together. Ryan and I just connected through a spiritual-ancestor type of vibe, and this film was the opportune time for us to work together. Ludwig is an amazing person and musician too; I’m a fan of everything he does.

So they were leaving to go shoot the movie, and Ryan called asking me to do the song. We got together that day and he gave me the concept of the film. I never read the script before I wrote the track, which I was used to from working with John Singleton on Boyz n the Hood and Higher Learning.

What did Ryan share about the movie?

Ryan told me about his uncle loving the blues and that the film was a love letter to it. It was full circle how it came around through Ryan — my family is from Monroe and Shreveport, Louisiana. When he told me about the song, I’m thinking I can go back to the studio and work on it and maybe send it to them next week. But he was like, Can you do it now? So I ended up just recording it myself.

I’ve actually had the song’s concept in my head since I was probably 19 or 20. The lyric “they say the truth hurts, so I lied to you,” that’s younger me lying to a girlfriend. It only makes sense in a blues song. I’ve always had these blues references because I grew up in a blues house. My dad loved the blues; my stepdad loved the blues. There’s a quartet group I used to play in called the Gospel Hummingbirds, and all of our songs were based off of Delta blues. For “Lied to You,” I brought my Baptist-church roots into it and the spirit just took over. And then I never heard it again until Ryan showed me the film two weeks ago.

What was your reaction to seeing Miles Caton perform the song?

I was amazed, inspired, and thinking about a lot of ancestors. I know a generation that actually picked cotton, like they do in the film. The quartet groups I played for when I was super-young all had men in their 50s who talked about picking cotton.

Ryan premiered the movie in Oakland at the Grand Lake Theater. It was a crazy experience — the best homecoming I ever had. Watching the scene itself was powerful. It was a 360-degree circle of ancestors and Black people with drums, rhythm, and all those spiritual things that I used to hum in Baptist church. That’s what the Black gospel is; that’s what the blues is.

That scene shows the whole trajectory of how Delta blues is at the seat of modern Black American music. Your own career spans a wide breadth of American music. Did you feel any kinship in seeing so many Black genres of music celebrated onscreen?

Yeah, I did. When I looked at that scene, that was my life. Ryan was talking to me about how church people were kind of against those who sang the blues, because they thought they were “singing for the devil.” I’m like, Damn. This is how I grew up. I grew up in the church and started playing around with genres, and everybody started telling me, “You’re playing for the devil.” So writing the song wasn’t a stretch for me. I didn’t have to think about it.

Sinners is a horror film with vampires who represent the relationship between whiteness and the blues. Do you feel like that the desire to mimic and extract from Black music still exists?

One hundred percent. We are the leaders of the movement of music. We’re the ones who created the blues — we dance, we move, we run, we jump, and we do it so much better. And the culture-vulture thing is real. If Stevie Wonder sings a run, everyone else is going to start doing runs. I mean, you got a New Edition, then you got New Kids on the Block; you got Usher and then you got Justin Timberlake. But in Black music, you’ve got to be really good for us to go get it; you can’t play around. You got to hit us in the heart like Frankie Beverly’s “We Are One.” There’s a lot of great, amazing white guitar players who play the blues and can play a ton of licks, but none of them are going to play like Eric Gales, Buddy Guy, Albert King, or Little Jimmy King. Our people went through so much; you can’t copy the struggle. It’s okay that we lead the pack and that everybody follows. But I always want to make it hard for you to copy me. If you don’t want somebody to copy, go with your spirit. You can’t copy that.

“I Lied to You” also brought to mind the work you’ve done with Beyoncé on Renaissance and Cowboy Carter bringing together different Black genres. How do you try to go about mixing and matching all these different sounds?

I’ve been fortunate to collaborate with good artists who just wanted to work hard. I find it easier to work with people who are working toward a common goal. I’ve been working with Syd from the Internet. She’s her own producer, writer, engineer — she does everything. She doesn’t need me. But she invited me into her room. Same thing with Beyoncé. When you work with somebody like Bey, the way she talks about music, you feel like you are at school. That’s the kind of room you want to be in until you die. And then you want to present the best. You want to think about Shalamar, S.O.S. Band, Prince, Herbie Hancock. You want to think about the best jazz players, D’Angelo, hip-hop, your mom, your uncle, everybody. When you present something to an artist, you want them to feel all those people when you’re not even noticing it.

You have an upcoming one-man show kicking off at the Apollo next month, where you’ll chronicle a three-decade body of work. How do you wrap your head around trying to paint homage to the broad discography you’ve contributed to the world?

I wanted to do this for a long time. I was always amazed by comedians like Richard Pryor standing on the stage with a microphone and a glass of water. The show is going to be about the music and what I was going through at those times. This gives people an opportunity to meet me one-on-one. My music has a thread to it — that we are all common people on the street.

Related

“I’m like, ‘Damn. This is how I grew up.’”