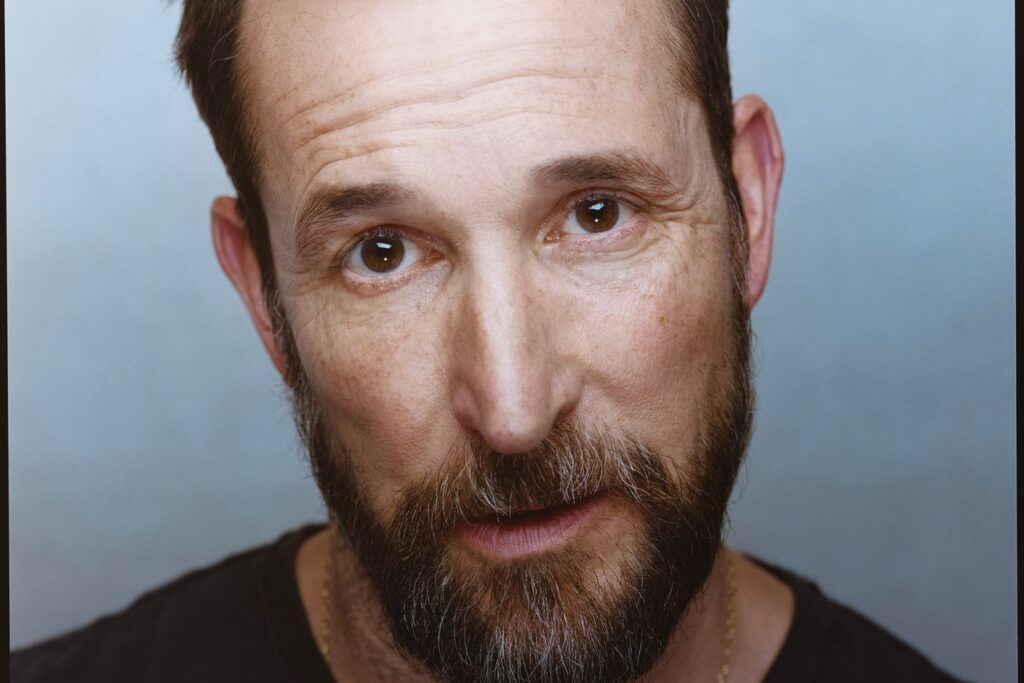

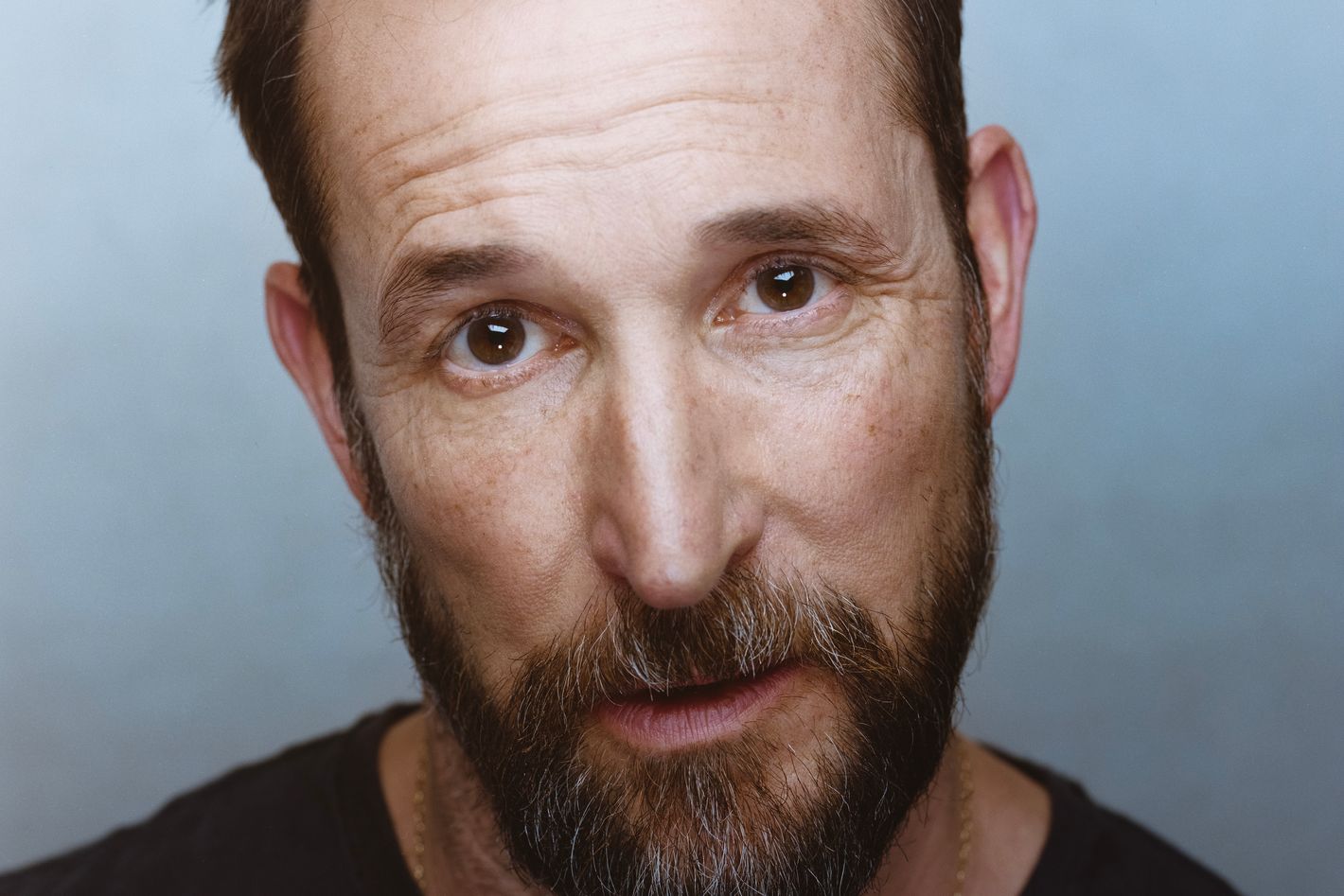

Noah Wyle is having a nightmare of a day on The Pitt. His character, Dr. Michael “Robby” Robinavitch, has been plagued with knee-buckling COVID flashbacks, forced to fire a trusted colleague, watched numerous children die, and continues to butt heads with a hospital administrator obsessed with patient-satisfaction scores. In the episode “6:00 P.M.,” everything gets worse in a typically American way: There’s an active shooter at a nearby music festival, and the ER Robby oversees is bombarded. Blood pools on the floor and soaks through doctors’ scrubs; ambulance sirens overtake the sound mix. Robby, who previously strode from patient to trainee with unassailable empathy and decisiveness, looks lost. He was supposed to attend the festival with his ex’s son, and he hasn’t heard from the 17-year-old. His face, so often calm and ready, crumples into despair. Things aren’t going to be okay. It’s a hell of a way to end an episode of a series that has, to this point, won over audiences with the familiar, assured smile of a former ER star and the idea that health care is a human right, not a profit generator.

“What you’re seeing is the water level in his eyes. He’s almost going under,” Wyle says. “We gave the press the first ten episodes. Everybody’s enjoying this train ride. I’m the only one that knows we take this train over a cliff.”

There are always medical procedurals on TV; each of the big four networks currently has at least one. The Pitt is Max’s, the product of a brain trust that worked together on the juggernaut ER and includes Wyle (also an executive producer and writer on the show), creator R. Scott Gemmill, and executive producer John Wells. The Pitt has the hallmarks of an old-school television hit: It follows a weekly release model instead of streaming’s more customary binge. It mirrors the structure of the popular early-aughts show 24, with each claustrophobic, fluorescent-lit episode unfurling as one hour inside the Pittsburgh Trauma Medical Center’s emergency room. It features a star from the second-longest-running prime-time medical drama of all time. Viewership is wide, reviews are enthusiastic, and in more present-day terms of success, social-media posts about Wyle are thirsty. The show’s unabashed story lines — about abortion, and access to health care for trans people, and racial bias among medical professionals — run counter to the real world’s trend toward DEI abandonment.

Wyle and I are sitting in the Players Club, the private actors’ society in New York City that he’s been a member of since he skyrocketed to fame as Dr. John Carter on ER. The club was founded by Edwin Booth, elder son of the acting dynasty best known for producing John Wilkes. Wyle has been transfixed with the Booths since his teens, back when he was acting in plays with his family or at school, and decades on, he feels at home among their possessions. He points to the legendary skull of the horse thief Fontaine, which Edwin used to perform Hamlet and is now sealed off behind a velvet rope. “The skull used to be right here — you used to be able to pick it up,” he says. He and his friend Steven Weber, another prime-time leading man from the ’90s who is currently appearing on successful medical procedural Chicago Med, would “fuck around” with the skull, Wyle says, letting out a raspy laugh that bursts forth whenever he’s making fun of himself. (That cackle can be a bit self-loathing, too, like when he claims he looked like a “hostage” in a recent appearance on The Kelly Clarkson Show.)

We’re chatting six days after The Pitt wrapped in early February. The next week, Wyle will report to the series’ writers’ room to begin work on season two. He is used to these long-term gigs; he dedicated four years to the TNT series The Librarians and Falling Skies, respectively, and 15 years to ER, playing a privileged kid who starts out as a fumbling medical student, grows into a politically engaged resident, and ends the series as a stoic attending physician. “The John Carter character arc that extends from the pilot episode to the finale is one of the biggest dramatic arcs you can possibly play,” Wyle says. ER attracted nearly 35 million weekly viewers, but most of the original actors, like George Clooney, left the show after a few seasons. Not Wyle. He stuck around for a hulking 254 episodes, taking a two-season break only after the birth of his son Owen in 2002. ER was the monoculture, generating breathless attention over its characters’ romantic entanglements, as well as countless magazine covers, beginning with an October 1994 Newsweek that declared ER “A Health-Care Program That Really Works.” During the series’ run, he had to turn down movie roles in Saving Private Ryan and Clooney’s Good Night, and Good Luck. “I had a really great first act in my career, and got associated with a show that ran for a really long time. I stayed with it,” he says. “What came after that came after that.”

What came after was a string of “almost Jimmy Stewart characters” on basic cable. Wyle’s sweet spot is playing normal guys who radiate knowledge and a touch of mischief — the types who could lead you into war or make a college lecture interesting. (His longtime colleague, the costume designer Lyn Paolo, says she let the actor give her stitches once; she’d cut her finger on the set of ER, and writer and co-executive producer Dr. Joe Sachs agreed to supervise the suturing. “We worked hard, we played hard back then,” Wyle says. “We were all sewing each other up.”) “He’s extremely intelligent, and that intelligence comes off,” Wells says. “It’s not just empathy. It’s an ability to listen, and a stillness that he brings as an actor, which is a skill that goes unnoticed sometimes.” Falling Skies and The Librarians had a fraction of ER’s viewership, but they made good use of Wyle’s level gaze and pitched-down tone, and attracted their own niche sci-fi/fantasy audiences — the kinds who show up to comic-cons and buy tie-in novels. “I got kind of at peace with not feeling like I was doing work that was in the Zeitgeist,” Wyle says.

Then in March 2020, as COVID was decimating the country’s medical infrastructure and shuttering Hollywood, Wyle started receiving dozens of Instagram DMs from first responders who knew him from ER. Some messages were “confessional” about the difficulty of the work, some were complaints about how inadequate that era’s pot-banging appreciation felt. Many were a “Hey, Carter, we could use you out here” appeal. “The volume was sort of directly proportional to my depression at the time,” Wyle says. “I felt useless, and I was being acknowledged, and that was a weird combination for me to reconcile.” Wyle eventually shared the messages with Wells and Gemmill, and the three of them met intermittently over the next few years to talk about working together again. The first idea was a project affiliated with ER and Dr. Carter, which fell apart in April 2023.

Wyle can’t share many details about this because he, Wells, and Warner Bros. are being sued by the estate of author and ER creator Michael Crichton, which has claimed that The Pitt is an unauthorized reboot of ER. Wyle insists The Pitt is an entirely separate endeavor. “I just wanted to put this spotlight back on these first responders. I wanted to put the attention back on this community that needed it,” Wyle says. “And Wells goes, ‘We could still do that.’” They set out to make something “radically different” from ER, with a “radically different guy, and have everything be able to live on its own.” The Pitt is set in Pittsburgh, not Chicago, and the season unfolds in real time, with overlapping crises ratcheting up tension as the cast careens around the sterile white set. Drs. Carter and Robby are indeed both medical professionals and educators, but in temperament, attending physician Robby has a grizzled, earthy, seen-some-shit air that distinguishes him from the desperate-to-prove-himself, low-key womanizer Carter. (Plus, Robby occasionally wears a little pair of glasses that accentuates a menagerie of serious and comical reaction faces; Wyle reassures us they’ll get more play in season two, “because my eyes are getting worse and worse.”)

In May 2023, the trio met for the first brainstorming session for The Pitt, only for the WGA to announce its strike the next day, sending Wyle out onto the Hollywood picket lines around Netflix and Warner Bros. “I had 192 days to walk in circles thinking about what kind of work I wanted to do, and who I wanted to do it with, and what I wanted it to feel like, and the impact I wanted it to have,” Wyle says. “That was the incubation, so that when we hit the ground, we hit it really running fast.” Fourteen months later, The Pitt debuted on Max, with Dr. Robby getting a hottie introduction, sunglasses shielding his eyes from the 7 a.m. light glinting off the gray in his beard as he walks to work. Wyle says he’s still surprised to have been cast as the lead when The Pitt shed its connections to ER. “I think of Max and HBO as sort of a big league that I haven’t been playing in for a while. This was just an answered-prayer gig.”

“Over the last five years, pretty much everything in streaming has had a movie star who’s agreed to be in the show,” Wells says. “And Noah, he’s very humble about himself. I don’t think he realizes just how large a star he actually is.”

Inside the ER, nicknamed “the Pitt,” Wyle’s Dr. Robby is the spoke in the wheel, the central point around whom everyone else revolves and from whom everyone else takes direction. It was a role he performed behind the scenes, too, as an executive producer and writer. “There’s an element of Noah’s personal experiences in a business that’s tough,” says Gemmill. “It lends itself perfectly for this character in terms of someone who’s been through so much and is still trying to keep doing it and pass it on to the younger people.” When The Pitt’s casting calls went out, Wyle attached a letter to each character breakdown, referencing director and screenwriter Robert Altman’s approach to ensemble pieces like M*A*S*H and Nashville. Unlike ER, whose cast talked openly in interviews about stealing scenes out from under one another and intimidating guest stars, The Pitt would be an even playing field for everyone. Any character, a lead or an extra, could be tapped for a major moment. “There’s no differentiation on a good set between foreground and background, or cast and crew. It’s just company,” Wyle says.

The Pitt was the first recurring TV gig for Patrick Ball, and he says Wyle created a “non-ego-ful” atmosphere where Ball felt comfortable getting physical during their characters’ confrontation at the end of episode “4:00 P.M.” Each episode is named after an hour of the characters’ shift, and they tend to close on bangers, scenes where the actors get a chance to wrestle the episode away from medical emergencies and toward their characters’ inner lives. In the scene, Dr. Robby is shocked to learn that his trusted senior resident, Dr. Frank Langdon (Ball), is stealing benzos from the unit; their altercation involves the normally cool Robby losing his temper and the supremely confident Langdon begging to keep his job. “We got in the hallway and just started walking around, pushing each other around,” Ball says. “Sometimes, there’s games with people trying to steer a scene in their direction. None of that. It was just like throwing the ball back and forth. You’re just playing.”

That scene is the start of Dr. Robby’s breakdown arc, intensifying with the “mass-cas” story line of “6:00 P.M.” Gone are the quirky ER regulars who razz Dr. Robby and the other staff members; in their place is a wave of gunshot victims who mirror what countless Americans have seen on the news, if not experienced themselves. Performing the back of the season was as emotionally grueling as you’d expect. “You’re covered in blood and you’re listening to a lot of screaming and crying. You don’t ever get a reprieve from it because you’re so immersed in it,” Wyle says. “That was the most difficulty I had in terms of juggling my responsibilities outside of work, because it was almost just like, What’s the point? I need to stay in this. I need to stay in it all the time.”

In 2012, Wyle was arrested at a Capitol Hill protest against Medicaid cuts, and he appeared in a 2016 PSA urging the Electoral College to remove Donald Trump from the ballot. He isn’t afraid to share some of his other opinions: He doesn’t care for billionaires meddling in government affairs and he supports a national health-care plan, which he says is “not a question of ideas. It’s a question of will.” But Wyle stops short of suggesting that story lines on The Pitt are partisan. (For the record, the episode featuring a man with brain worms wasn’t a jab at Health and Human Services secretary and anti-vaccine conspiracy theorist Robert F. Kennedy Jr., he says, just a coincidence.) “It wasn’t like we sat around in the room going, ‘What would really rile up America?’” he says. Instead, his “agenda” is “to call into question some of the misinformation that’s out there, that wants to call a medical fact an opinion.” Wyle himself wrote two episodes this season, including “3:00 P.M.,” in which two moms get in a fistfight about mask use. The story line wraps with the anti-mask mom needing surgery on her hand and acknowledging that she wants the doctors performing the procedure to be masked. That, Wyle confesses, was meant to be a statement. “Masks are important. They cut down on disease transmission. It’s a fact. It shouldn’t be a political position.”

Talk to Wyle long enough and an Old Hollywood, liberal-coded traditionalism comes out, especially in his beliefs that storytelling is an empathy generator and the people doing it should earn a living wage. He’s on a streaming series now, but he’s doubtful of any business model that ceaselessly prioritizes “unlimited growth.” “Our dads built something that was really great, and then we all looked at it and thought, Let’s break it and do something better,” Wyle says. “And then we came up with something better and bigger and totally unsustainable. And then we went, ‘What did Dad do?’ And then we rebuilt what Dad did. This whole thing feels very cyclical.” He wants to keep bringing work like The Pitt to Los Angeles, the city where three generations of his family (including his mother, a former orthopedic head nurse) have lived and which he recently saw destroyed by devastating wildfires. “I’ve been through a lot of shit in that city. I’ve never seen anything like that,” he says.

Maybe Wyle will eventually go out for movie roles again, or develop his own show, or produce other projects that inspire him as much as The Pitt. It’s difficult for him to think ahead, though, “when I have the career that I want right now.” Plus, he’s already come to terms with the idea that mainstream success at the level of ER might never come his way again. “Because I know it doesn’t lead to anything other than, you know, this.” I ask him to elaborate on what “this” means, and he tells me about how, after our meeting at the Players Club, he went back the next night, to “the space that I love,” winning at the pool table and drinking at the bar. He worried he’d fall and crack his head open during the drunken walk through the snow back to his hotel, and then he slipped in the shower after throwing up. He called his wife early in the morning, wondering if he had a concussion. She told him to go to the doctor. He jokingly replied that he basically is a doctor. “You can be on a hit show. You’re still going to slip in the shower and hit your head, piss off your wife,” Wyle says. “It’s just life.”

More ‘The Pitt’

On ER, Noah Wyle was a prime-time TV star. In the streaming era, he’s just happy to be part of the company.