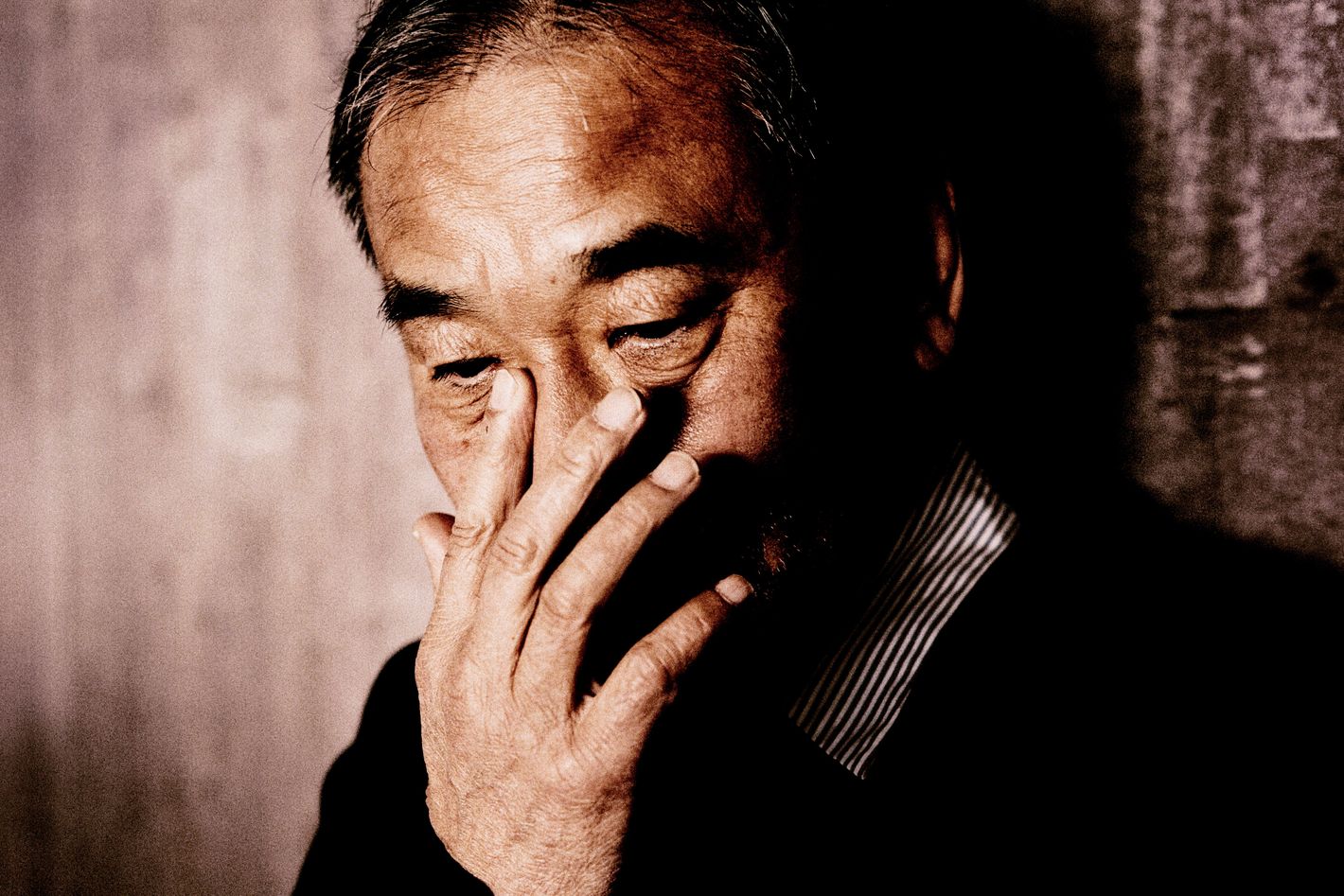

More than any other contemporary writer, Haruki Murakami has become the poster boy for a particular type of global novel — deracinated, stripped of local references that might stump international audiences, and generally written in a simplified form of its original language, the better to ease the process of translation. Odd as they are, his works epitomize a brand of contemporary fiction that’s been shaped, in one way or another, by the market forces resulting from 21st-century globalization.

In the last decade, though, Murakami’s warm embrace from the global market seems to have encouraged a certain maximalist tendency in his writing. The books have gotten longer and more pensive at the same time as they’ve been subjected to fewer cuts — witness the magnificently bloated 1Q84 (2011) or his most recent full-length novel, Killing Commendatore (2017). Clocking in respectively at 1,184 and 704 pages in English, these twinned monstrosities feel like radical experiments in doing the least with the most.

For many older writers, minimalism becomes an increasingly vital part of their continued practice. There is a word for this in Japanese, shibumi, that denotes an aesthetic of austere simplicity and effortless perfection, of doing the most with the least. But there isn’t much room in Murakami’s work for this lighter touch, in part because the strictures of “Global Literature” already enforce that restraint on its writers. It’s a problem that’s evident in two new works. The City and Its Uncertain Walls, released in Japan in 2023 and with an English translation by Philip Gabriel out today, reenvisions his 1985 novel, Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, which was published in English in 1991 in a translation by Alfred Birnbaum. In December, a new translation of that novel, which somewhat confusingly inverts the title, by Jay Rubin, will be released. Both books shed some light on the riddle of Murakami’s late style, which manages to project the quiet self-assurance of the old master at the same time as it embodies — in its hamfisted gestures, overreliance on bathos, and unflagging avoidance of subtlety — all the classic foibles of the literary hack.

The City and Its Uncertain Walls, Murakami’s 15th novel, began as a long story published in the literary magazine Bungakukai in 1980. Although disappointed with the story’s quality, Murakami would use it as a jumping-off point when composing his fourth novel, Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, which appeared in Japan in 1985. The 1991 English translation would help to cement Murakami’s burgeoning reputation in the West.

But the text that landed on American shores was an strange amalgam of competing visions and priorities, as David Karashima has detailed in Who We’re Reading When We’re Reading Murakami (2020), a wonderfully gossipy study that looks at the symbiotic relationship between literary market forces and the Murakami-in-English industry. What emerges most clearly from Karashima’s book is how, in the early days, American publishers — and indeed, Murakami himself — placed a premium on creating a readable and propulsive text, offering supreme ease of access for the native readers.

As they began to appear in English throughout the 1990s, Murakami’s novels generally had some of their weirder angles sanded off. While Birnbaum’s playful take on Murakami’s prose established the hip, colloquial style the author is still mostly known for today, his translation of Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World cut about 100 pages from the Japanese text. And when Jay Rubin translated The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle (1995), roughly 25,000 words were left on the cutting-room floor, while hefty structural changes were required to suture the remaining text together. (Rubin’s edits, as he’s explained, were a preemptive effort to stave off heavier cuts from the publisher.) All of this, as Murakami’s translators and editors at the time have attested, was done with saleability in mind. An invasive translation process, in other words, has always been central to Murakami’s success abroad.

Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, as its title suggests, is composed of two narratives that run in alternating chapters, syncing up in unexpected ways. Hard-Boiled Wonderland is a sort of goofy sci-fi pastiche following a Chandler-esque protagonist with the ability to encrypt information using only his brain as he plunges into a mystery involving competing data agencies; a half-mad professor and his attractive, though slightly overweight, granddaughter (a minor weight problem is basically her only defining trait); and subterranean creatures, known as Murks, that resemble the kappa of Japanese folklore. End of the World, is a muted fantasy that takes place in a medievalish town surrounded by a high wall in which the recently arrived protagonist is tasked with taking up the post of Dreamreader. For several hours a day, he sits in the town’s library and reads dreams, which happen to be contained in unicorn skulls.

Despite the book’s bicameral structure, it’s a quirky, propulsive read, a sort of postmodern riff on Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, an atmosphere that felt well-captured in Birnbaum’s breezy translation. In Rubin’s reworking of the text, a good deal of content has been restored, including descriptive digressions and, in the Hard-Boiled Wonderland chapters, several sexually suggestive conversations with the professor’s 17-year-old granddaughter. (“I couldn’t believe that showing my healthy erect penis to a seventeen-year-old girl would develop into a major social problem,” is by and large the sort of sentiment we’re dealing with here.)

One great benefit of a fresh translation is the opportunity to take advantage of a fuller knowledge of the author’s themes and motifs, which might not have been as obvious when the text was last translated. Birnbaum couldn’t have grasped at the time how fundamentally and importantly boring so much of Murakami’s writing is. Anyone who’s grappled with a few Murakami novels knows to expect gratuitous and essentially flavorless passages of rote description — meals are cooked; laundry gets folded; characters’ outfits are described in superfluous detail. Key plot points and developments are often reiterated in-scene. Structurally, this tedium is load-bearing. The long passages of banal detail in Murakami’s fiction are a sort of ballast, anchoring his precipitous swerves into the fantastic. This surplus of realism isn’t the fanciest trick, but it has served Murakami well over the years.

It’s a bit of a shock, then, to discover how much of this verbal wadding Birnbaum trimmed away. At one point in Rubin’s translation, we’re given a granular description of the narrator’s return to his apartment:

Back in my room, I put the groceries away in the refrigerator, tightly wrapping the meat and fish in plastic and freezing some for later. I froze the bread and the coffee beans, too. The block of tofu I floated in a bowl of water. The beer went into the refrigerator along with the vegetables, though I took care to keep the older vegetables closer to the front. I hung my clothes in the wardrobe and lined up the soaps and detergents on the kitchen shelf. Then I scattered a handful of paper clips next to the skull on the TV.

Birnbaum’s version, in contrast, is a miracle of concision: “Back at the apartment, I put away the groceries. I hung my clothes in the wardrobe. Then, on top of the TV, right next to the skull, I spread a handful of paperclips.”

Overall, what Rubin offers readers is a slower, more meditative novel. But meditations have never been Murakami’s strength. Unlike the wells that stipple his fiction, Murakami’s thoughts are not particularly deep. His ruminations on the nature of reality are those of a bright high-schooler or a middling stoner. Rubin’s self-professed goal of capturing “the clean rhythmicality that gives Murakami’s style its propulsive force,” as he wrote in his 2002 book-length study of Murakami, imbues Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World with a certain elegance, a degree of stateliness, that it doesn’t possess in Birnbaum’s translation. Unfortunately, this ends up drawing more attention to the basic thinness of Murakami’s thought.

Murakami’s new novel, The City and Its Uncertain Walls, is similarly underbaked, so much so that it feels less like a Murakami novel than a piece of fanfiction set in the Murakami expanded universe. The first third of the book is largely takes place in the faux–medieval village from Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. When the novel opens, its nameless protagonist is in his mid-40s and basically adrift. As a teenager, we learn, he had fallen hopelessly in love with a girl, and together they’d dreamed up the imaginary village. The book’s first part is essentially a curtailed rehash of Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World in which the sci-fi sections have been replaced by a dreamy and generic teen love story while the fantasy sections speed through the original book’s plot points.

The rest of the novel, blessedly, tells a fresh story. Having somehow returned, firmly, to the real world, the narrator decides to quit his job and start working in a library in a small, out-of-the-way town in Fukushima Prefecture. He’s hired by the former head librarian, Mr. Koyasu, a gentleman in his 70s who wears a navy-blue beret and a skirt. Mrs. Soeda, a librarian, is the only other named staff member. In her mid-30s, she is married to a local elementary-school teacher, which, as far as Murakami is concerned, is exactly how much you need to know about her.

That Mrs. Soeda is chronically underdeveloped as a character and seems to be simply a tool for the advancement of the plot isn’t surprising. Murakami isn’t so much a novelist as a fictional anthologist, collating various monologues delivered by his characters; some of these are riveting narratives in their own right, but many simply serve to explain what’s going on or clumsily advance the plot. But the instrumentality of so many of his characters seems to have reached a nadir in The City and Its Uncertain Walls. Mrs. Soeda’s role is strictly to give the reader information — about the town, about Mr. Koyasu’s past, and about the enigmatic teenager, known as Yellow Submarine Boy (after the Beatles-themed parka he rarely takes off), who gradually becomes the focus of the plot.

Before that happens, we’re force-fed Mr. Koyasu’s backstory. A native son and heir apparent to the local sake brewery, he’d fallen in love, rather late in life, with Miri, a woman ten years younger than him, “a secretary in either the Tunisian or Algerian embassy.” After a few years of marriage, a surprise pregnancy put an end to the long-distance nature of their relationship. The son they have, Shin, dies when he is 5 years old, having ridden his beloved red bicycle into the street, where a truck strikes him. Miri withers away in grief and eventually takes her own life by swallowing a nonlethal dose of sleeping pills, tying her legs up with nylon rope, and leaping into the local river.

It’s a mawkish, paint-by-numbers tragedy, the sort of thing Mr. Koyasu himself might have written, since, as we learn, he’s a bit of a novelist manqué, a dabbler in literature who never really found his true subject. You often get the sense, reading The City and Its Uncertain Walls, that Murakami is rehashing his own experience as a writer. Indeed, Mr. Koyasu’s failings as a writer-to-be map closely onto Murakami’s descriptions of his own writing career in Novelist as a Vocation (2022). “The first time I sat down to write a novel, nothing came to mind—I was completely stumped,” Murakami writes. “There was nothing, in short, that I felt absolutely compelled to write about.”

Just as Mr. Koyasu reflects Murakami’s writerly insecurities, Yellow Submarine Boy provides a vision of Murakami’s reading habits. An antisocial teenager with a savantlike memory, Yellow Submarine Boy sits in the library all day reading one book after another, “everything from Immanuel Kant to Norinaga Motoori, Franz Kafka, Muslim sacred texts, books on genes, Steve Jobs’s autobiography, Conan Doyle’s A Study in Scarlet, the history of nuclear submarines,” and so on. In its sheer omnivorousness, and even more so in its seeming randomness, this intake reflects Murakami’s own self-confessed reading habits as a young man. In the end, this leads to a novel that might be Murakami’s most navel-gazing work, and one that has the unmistakable feel of a coda.

This seems to be part of the reason The City and Its Uncertain Walls is such an unnaturally somber book. Except maybe for 1992’s South of the Border, West of the Sun, no previous Murakami novel has so clearly dealt with and inhabited the muddle of middle age. “I seemed well on my way to becoming one of those lonely middle-aged men who follows habits without really thinking about them,” the narrator remarks at one point. And while Murakami seems constitutionally incapable of pessimism, there are a few moments of weariness scattered throughout the book that feel significant, like when the narrator comments on a specific jazz tune being played in a café he frequents, only for the owner to respond that she doesn’t really know much about jazz — it’s only a radio station she plays. Murakami has always written perceptively of young love and the aimlessness of early adulthood, but only now, in his eighth decade, is he getting around to investigating the plight of the middle-aged.

All in all, The City and Its Uncertain Walls is a frustratingly literal book. Murakami is a sentimentalist at heart, and the novel isn’t shy about reminding readers that its titular walls are a metaphor, in part, for the similarly vertiginous barriers that separate one human heart from another. This schmaltzy dictum is comically literalized when it’s revealed that the café owner who becomes the narrator’s love interest is not only unable to have sex, but also wears a protective Spanx-like bodysuit. As a gesture at quirkiness, it feels tired and stridently complacent in the same way as the novel’s core bid for topicality — as its jacket copy asserts, the book is partly “a parable for these strange post-pandemic times.” As far as I can tell, what this amounts to is that most of the characters are lonely, and that at one point Yellow Submarine Boy explains that the wall around the imaginary town was built “to prevent an epidemic.” If this feels a little on the nose, rest assured that, as Murakami drives home with portentous italics, the epidemic is in fact a metaphor, “an epidemic of the soul.”

The Murakami shtick is on full display in The City and Its Uncertain Walls. Wells make an appearance. One character draws an elaborate map; another cooks spaghetti. There’s a family of stray cats and something weird related to ears. But most of these details are toothless, or at least unactivated. The mapmaking isn’t linked to Japan’s history of imperial aggression, as it is in The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, but to a pure fantasy world. No one climbs down into either well only to be transported to an alternate reality. The cats don’t talk; the ears aren’t subject to breathless description; and a character cooks not spaghetti with tomato sauce but “spaghetti with calamari and mushrooms.”

All of this adds up to a mere patina of weirdness, not the deep, bracing strangeness to be found in stronger works like A Wild Sheep Chase (1989), with its enigmatic, half-human Sheep Man, or the postmodern fantasia of Kafka on the Shore (2005), in which the whiskey mascot Johnnie Walker is depicted as a cat-killing personification of evil. Which isn’t to say this strangeness is entirely absent from The City and Its Uncertain Walls. After Mr. Koyasu’s wife disappears, he enters their bedroom and pulls back the covers of her bed to confirm she isn’t simply sleeping. “And instead of her, he found two long scallions lying there. White, thick, splendid scallions,” Murakami writes. “She must have placed them there. He was, naturally, shocked, and frightened by the sight.” As I read on, approaching the end of the book, it was with a vague sense of dread I couldn’t entirely place, until I realized that I was waiting, in patient agony, for those scallions to return, for Murakami to pound them into a blandly explicit paste. Then I was done, and I found that, whether through wisdom or accident, he had left them there, unexplained and probably inexplicable, like the best of his fiction.

Two new works read more like fan fiction set in the extended Murakami universe than the thrillingly strange novels he’s famous for.