Bruce Dickinson puts his pants on, just like the rest of us, one leg at a time. Except once his pants are on, he makes gold records. Such is the premise of Saturday Night Live’s Mount Rushmore of a sketch “More Cowbell,” with the music producer (Christopher Walken) trying to iron out the melodic kinks of Blue Öyster Cult’s enduring hit “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper” alongside the band. You see, Bruce has a good ear and even better instincts. As soon as Gene Frenkle (Will Ferrell) begins to bang that cowbell and explore the studio space with his body, his bandmates are distracted and furious that it’s drowning out the other instruments. But all Bruce hears is a “dynamite sound” that needs to be cranked up to 11, and he doesn’t understand why this additional percussion isn’t being met with greater enthusiasm. “I’m telling ya, fellas,” he declares, “you’re gonna want that cowbell.” There’s a prescription that needs to be filled for his fever, too.

Airing as the final sketch of the Walken-hosted April 8, 2000, episode, “More Cowbell” has leaped from Studio 8H’s gold-plated diapers into cultural ubiquity. The phrase has even merited an entry into the dictionary. (Idiom, informal: “An extra quality that will make something or someone better.”) Donald “Buck Dharma” Roeser, Blue Öyster Cult’s co-founder and front man who wrote “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper” for their 1976 album, Agents of Fortune, has managed to maintain a healthy relationship with the sketch, but he admits the fate could’ve been a lot different if he didn’t find the premise genuinely humorous. “It’s been a 25-year journey with the cowbell and riding that horse,” Buck Dharma explains. “I can’t complain about any of the history and what’s happened. It’s all good.”

The sketch aired in April 2000. Prior to this moment, can you tell me a little bit about how Blue Öyster Cult was navigating the new millennium? How did you view yourselves as a band nearly 30 years into your history?

Of course we became — I’m looking for the right word — I want to say an “adult” or “mature” group, because we’d been together longer than most pop groups stay together, at least in my experience of a lifetime. The fact that we’ve been together 52 years now is ridiculous. But it’s been a great ride and I have very few regrets, if any. But in 2000, we were below the pop radar. We weren’t selling records by then. We were still recording but to a specialized audience. We were doing very well with touring. We’ve always done well with touring because we were a great live act, and people would come out and see us and the fans are loyal. Once the internet became something, our popularity got a big boost. Even as it killed the legacy-record business, it was doing very well for their personal awareness with new audiences.

How specialized was your audience?

Even in our heyday, Blue Öyster Cult was always a rarefied choice among rock-record consumers. We never really had the double-platinum or ten-platinum record like the biggest artists did. But our brand of humor, the way we presented ourselves, the way we sounded, and the way all of us played, people just liked it. I’ve always been grateful to have made a good living doing this.

Were you ever invited to play SNL as a musical guest? It seems like an oversight that you never swung by in the 1970s.

We never got the call. I don’t know how those decisions are made as far as who gets on the program and why, but I would’ve certainly done it. We did a few TV shows in our time, but not SNL.

The very first words spoken by the narrator in “More Cowbell” are “After a series of staggering defeats …” Of course, this is silliness to tee up the rest of the action, but looking back at Agents of Fortune, what would you say were the most taxing elements of its creation?

I would say Agents of Fortune was an evolution of the band’s development more than anything else. The big difference for Agents was the invention of affordable multitrack tape recorders. All the band members got their own four-tracks at home. So when we wrote songs, we could bring them in with more thought-out arrangements than we had done in the past, which was basically: You’d come in with a guitar and an idea, you’d explain it to everybody else, and we would arrange it all in real time and see if it worked. There’s something to be said about working that way, but the difference for Agents is that the songs were, in turn, more considered and fleshed out by the time they were brought to the band, even if those songs demanded more work afterward. They were actual, realized visions of the composer’s intent.

Also, we recorded at the Record Plant in New York City, which was the gold standard. That was the first time we recorded in that studio. We’d previously used Columbia’s old studios in the city, which was required as part of their labor agreement with their people. John Lennon, Aerosmith, Cheap Trick, Blondie, and a lot of the really successful acts were recording there. To be around those types of artists put things into perspective real quick.

Did you have any memorable studio run-ins?

We had a friendly rivalry with KISS. Frankly, it was just nice to meet other artists and say hello. I was born and raised on Long Island and not living in the city, so going to Manhattan to record became a nice social thing.

What moment in the recording studio do you wish cameras were actually there and rolling to capture?

We always enjoyed working in the studio, but it was fairly purposeful, businesslike, and pleasurable when you knew you recorded something that sounded great on the playback. For “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper,” the iconic guitar riff just came out of my fingers at a time when the tape recorder was in front of me. I guess that could’ve been my Paul McCartney in “Let It Be” moment. I was able to capture it and realize it was the start of something. The first two lines of the lyrics just sort of sprang into my head. From that, I had the idea to write a song about a love story that survives the death of one of the lovers. So that was the crux of it all.

What do you recall about the conversations revolving around the cowbell inclusion for “(Don’t Fear) the Reaper”? Did you always understand the instrument’s vision?

In reality, the cowbell was an afterthought on the part of David Lucas, who was one of the producers of that record. He thought that the groove in the verses could use a stead-four on the floor accent, because the drum part didn’t sound quite like that. Also, it wasn’t unusual to put a cowbell on a song. It wasn’t an idea that was unique or unheard of. I’ve never met Will Ferrell, but I would love to ask him how he conceived the idea of the cowbell, because the cowbell has become such an iconic cultural touchstone.

The sketch aired in the early hours of Sunday morning. How soon after did you take notice of it?

When the sketch aired, I wasn’t watching television, but my wife got a call from her mother who was still up that late and watching it. She said, “Oh my God, Donald is on television.” So we were a bit confused and turned SNL on and, of course, it wasn’t me. It was SNL lampooning the song and doing a sketch about it. I saw about the last 25 seconds of it. It wasn’t long after that I was able to get a VHS tape of the whole episode.

When you finally watched the full sketch from that VHS tape, what was your gut instinct about how you felt about it?

My first feeling was relief — relief that it was funny and relief that it wasn’t too cruel on the band. SNL had done some rather cruel things about Neil Diamond and other artists over the years, so I was happy it was actually hilarious. While it poked fun at Blue Öyster Cult, it wasn’t mean-spirited at all.

There’s a lot of breaking in the sketch — Jimmy Fallon, as always, is a big offender despite having two lines. Do you feel this enhances the hilarity of “More Cowbell,” or do you wish everyone kept straight faces?

Christopher Walken is so amazing in the sketch that I don’t see how I could have not laughed if I had been there. When the cast breaks, I think it makes it funnier. I don’t think anyone could have done it as well as Christopher Walken. He’s been on SNL a lot of times, and every time he’s on, he’s funny because he’s got that unique delivery and a real comedic sense.

Did any of your peers in the music industry express jealousy that this gave Blue Öyster Cult a resurgence of interest? I never know if there’s a competitive aspect to this sort of thing.

Not to my knowledge. Nobody has said anything to my face. I don’t know if you’d wish it on anybody, but certainly we’ve had to live with the cowbell whether we liked it or not. It just overtook the band in a lot of respects in the same way when people come up to Christopher Walken, who’s had such a storied career, and all they say to him is, “I need more cowbell.” I’m sympathetic to that. I have never contested the basic hilarity of the sketch.

Are your fellow band members as accepting as you are about this?

Sometimes you just get carried along by the culture. You don’t really control it. We’re all riding the worm like in Dune. The worm knows where it’s going.

Did your relationship with the song change in the aftermath of this sketch at all?

The first change was we began playing the cowbell in “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper” live. For 20-odd years, we didn’t use a live cowbell for our shows and never considered it. We had to play the cowbell because there was just no getting away from it. I’m grateful that as significant as the sketch is — because after 25 years, it still is — it didn’t kill the song, its original intent, or its original mood. It’s still used as a cue in horror movies when you want that mysterious and metaphysically uneasy vibe. So I’m glad the sketch didn’t kill the song and didn’t make it one big joke.

Will Ferrell has said, quite seriously, that Christopher Walken told him he ruined his life with “More Cowbell” because he’s been constantly inundated with quips from people about it. As someone else who’s been affected by this piece of SNL history, what advice would you give him?

It’s funny to think about. I feel bonded to Will and Christopher in a way, because we’re all at the mercy of the cowbell sketch in different ways. I feel a little bit of kinship and sympathy with them. Will’s character, Gene Frenkle, was made up. We dedicate the song to him sometimes. But I would tell Christopher: It’s all bearable, I suppose. Blue Öyster Cult got through it and we persevered. When we play “Reaper,” people still mimic playing the cowbell, and we had to ban people from bringing actual cowbells to the concerts. But, again, it’s a tiny cross to bear.

Did you ever favor shirts as tight-fitting as Will’s fictional cowbell player?

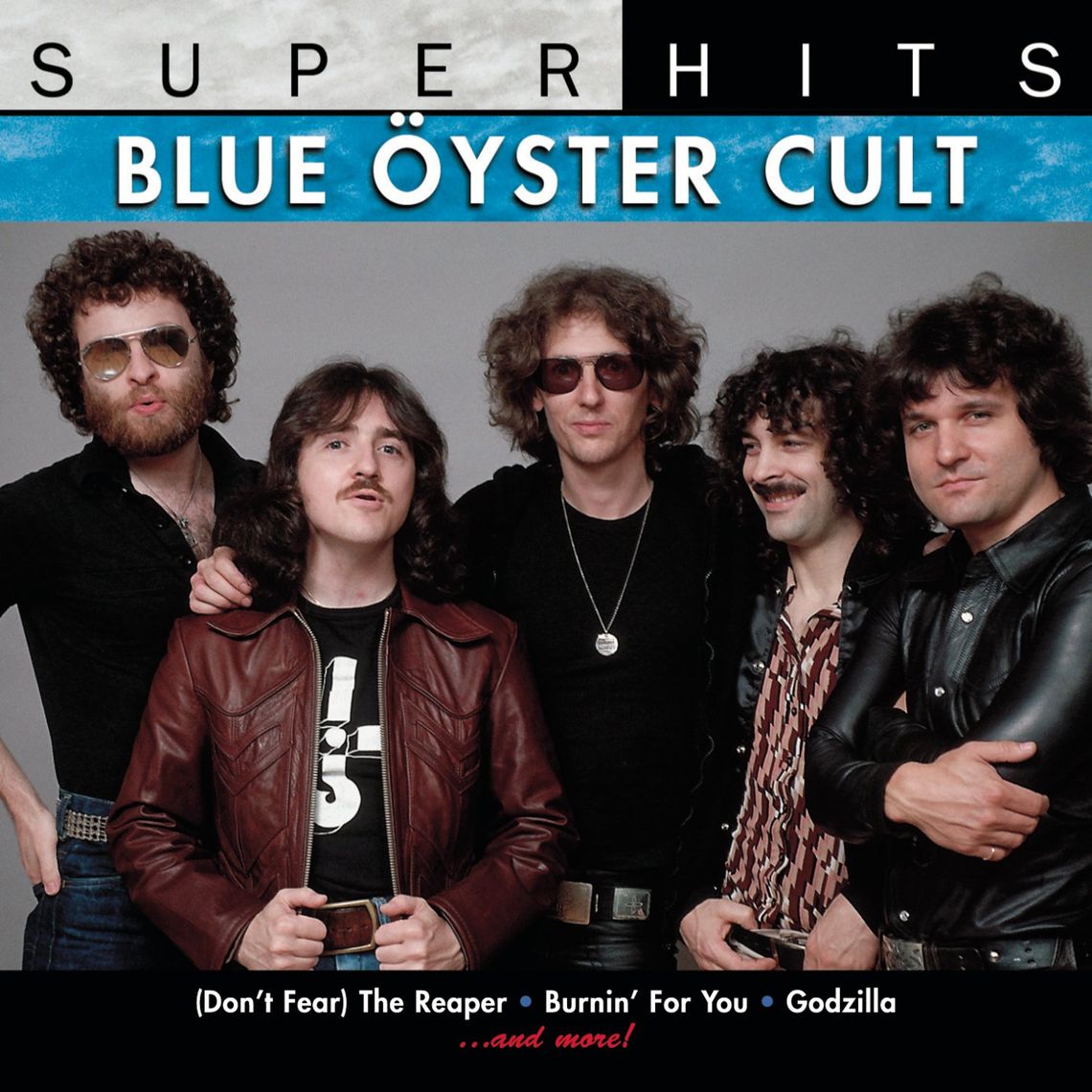

Maybe. The costumes in the skit were patterned after a photo of a greatest-hits compilation record we had. Bruce Dickinson, who’s the producer in the sketch, was actually a Sony legacy staff producer who assembled that greatest-hits record. He wasn’t actually the producer of Agents of Fortune, but all the outfits were copied from that photo. So you could see the photo and judge how tight.

This is tangentially related to our discussion, but I was keen to bring it up anyway: I was reporting from Cleveland for this year’s Rock Hall induction and talked with some Blue Öyster Cult fans who lamented how the band hasn’t yet been nominated. How do you view the organization? Is this an achievement you’d like to be a recipient of ?

I certainly wouldn’t mind being inducted, but I’m not holding my breath. I assume that Blue Öyster Cult is just not meeting whatever criteria is necessary to get in. Maybe there’s not room for everybody else. I know they’re down to putting people in posthumously now, so it’d be nice not to be dead before they do it or not.

In hindsight, do you think the song could’ve indeed used a little more cowbell?

I think the cowbell was just as loud as it should be.

Related

- SNL’s Lenny Pickett Is a Sax Machine

- Seth Meyers’s Proudest Milestones and Wisest Comedy-Writing Hacks

Twenty-four years later, Blue Öyster Cult’s front man on the agony, ecstasy, and relief of the SNL favorite.